IRAN MUST CLOSE DOWN THE 36-YEAR-OLD ISLAMIC REVOLUTIONARY COURTS

On The Anniversary of The First Revolutionary Executions in Iran

IRAN MUST CLOSE DOWN THE 36-YEAR-OLD ISLAMIC REVOLUTIONARY COURTS

“The Revolutionary Courts were born out of the anger of the Iranian people, and these people will not accept any principles outside of Islamic principles. There is no room in revolutionary courts for defense lawyers, because they keep quoting laws to play for time, and this tries the patience of the people … .”

“The Revolutionary Courts were born out of the anger of the Iranian people, and these people will not accept any principles outside of Islamic principles. There is no room in revolutionary courts for defense lawyers, because they keep quoting laws to play for time, and this tries the patience of the people … .”

Hojat-ol-eslam Sadeq Khalkhali,

Head of the Extraordinary Revolutionary Tribunal, May 13, 1979

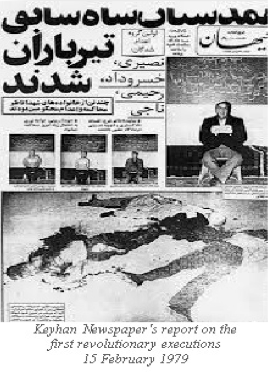

Thirty six years ago, on February 15th, 1979, a Revolutionary Islamic Tribunal held its first session in Tehran. The goal of this Extraordinary Tribunal, set up in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Iranian monarchy on February 11, 1979, and headed by a Shi’a cleric, Sadeq Khalkhali, was not to dispense justice. The new revolutionary regime, led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, used the ad hoc Tribunal to exact revenge, punish those deemed to oppose the revolution and its moral values, and to spread fear among the population. 36 years later, by doing away with due process of law and, in particular, the right to defense, these Revolutionary Courts continue to silence dissent and to spread fear.

Sadeq Khalkhali was appointed by Ayatollah Khomeini, as Shari’a Judge and was instructed “to issue Shari’a-based rulings. For months, no specific procedures were devised for the Revolutionary Tribunal. Its jurisdiction was determined by the religious judge’s interpretation of Shari’a (Islamic law based on the teachings of the Qur’an, the traditions of the Prophet, the 12 imams, and the teachings of Shi’a scholars). Arbitrariness, therefore, became rule, taking a toll on the lives of Iranians, as Ayatollah Khalkhali roamed the country.

Sadeq Khalkhali was appointed by Ayatollah Khomeini, as Shari’a Judge and was instructed “to issue Shari’a-based rulings. For months, no specific procedures were devised for the Revolutionary Tribunal. Its jurisdiction was determined by the religious judge’s interpretation of Shari’a (Islamic law based on the teachings of the Qur’an, the traditions of the Prophet, the 12 imams, and the teachings of Shi’a scholars). Arbitrariness, therefore, became rule, taking a toll on the lives of Iranians, as Ayatollah Khalkhali roamed the country.

In a televised address on April 2, 1979, the Founder and Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic responded to those who criticized the Revolutionary Tribunal’s process:

“There should be no objection to the trial of these people, because they are criminals, and it is known that they are criminals. All this about a lawyer being needed and that their pleas should be listened to — these are not people charged with crimes; they are criminals.”

In such a context, crimes could be defined retroactively and the Revolutionary Tribunals operating across the country tried thousands without clear charges, evidence, and lawyers. Convicts could not appeal their sentences and, for those who were sentenced to death, the execution often took place shortly after their convictions.

Such was the case of Dr. Akbar Bahadori, a general surgeon and orthopedist in the armed forces, remembered today for the hospitals he founded in Arak and Tehran. According to the daily Kayhan, Dr. Bahadori, a deputy from Arak in the Parliament before the revolution, was interrogated for twelve hours by the Revolutionary Tribunal of Arak before being executed on May 10, 1979. His charges, as reported in a 1980 Amnesty International report, included:

Such was the case of Dr. Akbar Bahadori, a general surgeon and orthopedist in the armed forces, remembered today for the hospitals he founded in Arak and Tehran. According to the daily Kayhan, Dr. Bahadori, a deputy from Arak in the Parliament before the revolution, was interrogated for twelve hours by the Revolutionary Tribunal of Arak before being executed on May 10, 1979. His charges, as reported in a 1980 Amnesty International report, included:

“collaboration with the ousted regime and trying to re-establish the Shah’s ‘idolatrous’ rule over the weak and defenseless people; collaborating with SAVAK; taking wrong decisions in parliament; bringing pressure to divide the people; crimes against the people and the revolution.”

Nothing much is known about Manuchehr Adibpur, who was charged in Shiraz with “active participation in the murder of the people and suppression of prisoners,” as well as an “illegitimate relationship,” and executed on July 5, 1979. The itinerant religious judge, however, explained the judicial process leading to his execution, including the fact that he never saw Adibpur’s file:

“I requested that the Islamic Revolutionary Prosecutor of Shiraz give us what they have at the Revolutionary Tribunal. Unfortunately, these cases were not passed on to us, and, therefore, I sentenced five people to death, based on what was available at the prison or the Islamic Revolutionary Guards headquarters,… I did not think it was even that necessary to examine their cases, anyway.”

“I requested that the Islamic Revolutionary Prosecutor of Shiraz give us what they have at the Revolutionary Tribunal. Unfortunately, these cases were not passed on to us, and, therefore, I sentenced five people to death, based on what was available at the prison or the Islamic Revolutionary Guards headquarters,… I did not think it was even that necessary to examine their cases, anyway.”

When his peer dared question the legality of his action, Khalkhali’s response was clear:

“It must be said to him that it is none of his business. It would only be fair if I performed my duty to defrock this pseudo-cleric so that other pseudo-clerics do not dare present themselves against the Islamic nature of Iran.”

Determining offenders’ guilt was not the primary role of the courts, and Ayatollah Khomeini was very clear about those brought before them. In the official decree, formalizing the creation of the Revolutionary Courts on June 17, 1979, the Ayatollah stressed:

“You must convene a revolutionary court via the Judiciary. … Their trial must not last longer than two days. They are [already] convicted, but their trial must be held in the presence of domestic and foreign reporters. Peace be upon you.”

Mandated by the Spiritual Leader, the Shari’a Judge was only carrying out his duty diligently.

The Islamic Revolutionary Tribunal of Saveh found Razieh Fuladi, mother of four young children, guilty of adultery, and had her executed on August 30, 1979, three days after her arrest. Her husband took his grief public, noting that she had been flogged and forced to confess.

Ali Amirshekari, a communist executed on August 23, 1979, was convicted as a “corruptor on earth and at war with God and his prophet” by the Revolutionary Tribunal of Kerman, for “encoded communication with counter-revolutionary groups in Kurdistan and Khuzestan; open opposition [to the regime]; and plotting against the Islamic Republic of Iran.” Non-governmental sources attribute his execution to his refusal to denounce, on television, the activities of his brother.

Ali Amirshekari, a communist executed on August 23, 1979, was convicted as a “corruptor on earth and at war with God and his prophet” by the Revolutionary Tribunal of Kerman, for “encoded communication with counter-revolutionary groups in Kurdistan and Khuzestan; open opposition [to the regime]; and plotting against the Islamic Republic of Iran.” Non-governmental sources attribute his execution to his refusal to denounce, on television, the activities of his brother.

19-year-old Jalil Golandami, a registrar for the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran (PDKI) in Mahabad, was arrested by the revolutionary guards without a warrant on September 27, 1979, at 5:00 p.m., along with a number of other young people. He was executed by firing squad as a “corruptor on earth” and an “enemy of God” eleven hours later, at 4:00 a.m.

19-year-old Jalil Golandami, a registrar for the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran (PDKI) in Mahabad, was arrested by the revolutionary guards without a warrant on September 27, 1979, at 5:00 p.m., along with a number of other young people. He was executed by firing squad as a “corruptor on earth” and an “enemy of God” eleven hours later, at 4:00 a.m.

Nothing much is known about the case of Karim Aqayun, except that he was executed at dawn, on July 30, 1980, after the Islamic Revolutionary Tribunal of Dezful declared him a “corruptor” for “sedition,” “drinking,” “selling alcoholic drinks,” and “threatening and terrorizing.”

Ayatollah Khalkhali was not the only judge dispensing death sentences in these extraordinary tribunals. To handle the cases of thousands of detainees, theological seminary students, with the equivalent of a high school diploma, were appointed as judges. The new recruits, estimated at 1000 in 1980 and 2000 by 1989, entered a judiciary, purged from university-educated judges lacking “commitment to the principles [of] the Islamic Republic.” The Revolution Courts were thus endowed with a cohort of incompetent judges, loyal to the leadership.

The activity of Revolutionary Courts was not limited to the early days of the Islamic Republic. Over the years, they sentenced to death, arbitrarily and summarily, thousands of citizens of all walks of life. Whether officials of the previous regime, political or religious activists, armed oppositionists, members of ethnic minorities, or people accused of sexual offenses or ordinary crimes, individuals brought before the Revolutionary Courts were denied proper means to defend themselves.

Today, the founding principles of the Revolutionary Courts are still in force, at the expense of the rights of the accused and in violation of Iran’s international obligations. The courts are faithful to the views of their founders’, for whom defendants, “whether right or wrong,” should not be defended. Judges continue to rely on Fatwas and religious opinions, issued by religious jurists who have multiple interpretations of the laws. As a result, there is a wide disparity in sentences handed down for the same offenses, making Iranians legally unequal before the law.

Today, the founding principles of the Revolutionary Courts are still in force, at the expense of the rights of the accused and in violation of Iran’s international obligations. The courts are faithful to the views of their founders’, for whom defendants, “whether right or wrong,” should not be defended. Judges continue to rely on Fatwas and religious opinions, issued by religious jurists who have multiple interpretations of the laws. As a result, there is a wide disparity in sentences handed down for the same offenses, making Iranians legally unequal before the law.

Regardless of reforms in 1994 and 2002, limiting their jurisdiction[1], providing the right to an attorney during trials, and a Court of Appeals to review the Revolutionary Courts’ decisions, judges continue to violate due process with impunity. They deny the accused the right to legal counsel when they deem necessary, accept coerced confessions as evidence, and issue politically and religiously motivated sentences. Further, the vagueness of laws regarding national security allows the Revolutionary Courts to try cases falling outside their jurisdiction, such as political and media crimes, whenever they wish to do so.

The young Ya’qub Mehrnahad, a civil society activist in Baluchestan, was executed on August 4, 2008, for promoting accountability and non-violence. His death was a tragedy for his extended family, and more so for his fifteen-year-old brother, who was imprisoned for publicizing his case.

The young Ya’qub Mehrnahad, a civil society activist in Baluchestan, was executed on August 4, 2008, for promoting accountability and non-violence. His death was a tragedy for his extended family, and more so for his fifteen-year-old brother, who was imprisoned for publicizing his case.

Shirin Alamhuli-Atashgah, a young Kurdish woman who was tried and executed on May 9, 2010, after being subjected to months of torture. She wrote to the judge, “You interrogated, tried, and sentenced me in your own language, even though I could not understand what was happening and was unable to defend myself.”

Shirin Alamhuli-Atashgah, a young Kurdish woman who was tried and executed on May 9, 2010, after being subjected to months of torture. She wrote to the judge, “You interrogated, tried, and sentenced me in your own language, even though I could not understand what was happening and was unable to defend myself.”

Zahra Bahrami was arrested in December 2009 during post-election Ashura protests. She was sentenced to death on drug charges by Branch 15 of the Islamic Revolutionary Court, and executed on January 29, 2011. She left behind a son and two daughters.

Zahra Bahrami was arrested in December 2009 during post-election Ashura protests. She was sentenced to death on drug charges by Branch 15 of the Islamic Revolutionary Court, and executed on January 29, 2011. She left behind a son and two daughters.

Mohsen Amir Aslani was a psychologist who gained popularity with his progressive views on Islam. A religious opinion declared him an apostate. The Tehran Revolutionary Court sentenced him to death for rape. Three rejection of his sentence by the Supreme Court did not prevent his execution on September 24, 2014.

Mohsen Amir Aslani was a psychologist who gained popularity with his progressive views on Islam. A religious opinion declared him an apostate. The Tehran Revolutionary Court sentenced him to death for rape. Three rejection of his sentence by the Supreme Court did not prevent his execution on September 24, 2014.

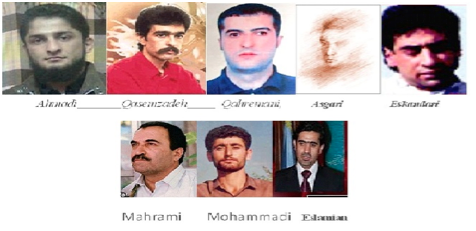

Bahram Ahmadi was a Sunni activist. He was seventeen at the time of his arrest. Mehdi Qasemzadeh was an ethnic Turk and an Ahl-e Haq follower. The insistance of a Garrison commander to shave the moustaches of the Ahl-e Haq soldiers was at the origin of events leading to his execution. Ramin Aqazadeh Qahremani, Mahmud Asqari, Nader Azarnush, Mansur Eskandari, Mehdi Eslamian, Dhabihullah Mahrami, Esmail Mohammadi, and Maqsud Q. are just a few among the thousands whose trials exemplify the proceedings of an extraordinary and unaccountable judicial body. None of these individuals were given a chance to properly defend themselves.

In fact, many religious leaders, sources of emulation, continue to see the limited possibility of defense, given the accused as a mere nuisance:

“The main problem of our judiciary is that it follows the style of the unhealthy Western judiciary system. In other words, once the file has been transferred from the police to the judiciary; there is the process of appointing a lawyer, followed by the lawyer’s advice to the offender to retract the frank recorded confessions made in the initial stages and to accuse the police of torture, and, subsequently, months of waiting for the trial, then the preliminary verdict, followed by the appeal court stage, and, ultimately, after several months, some feeble verdict is issued. Not only does this fail to act as a deterrent, but it serves to make the thugs and hooligans even more audacious.”

“The main problem of our judiciary is that it follows the style of the unhealthy Western judiciary system. In other words, once the file has been transferred from the police to the judiciary; there is the process of appointing a lawyer, followed by the lawyer’s advice to the offender to retract the frank recorded confessions made in the initial stages and to accuse the police of torture, and, subsequently, months of waiting for the trial, then the preliminary verdict, followed by the appeal court stage, and, ultimately, after several months, some feeble verdict is issued. Not only does this fail to act as a deterrent, but it serves to make the thugs and hooligans even more audacious.”

Ayatollah Makarem Shirazi, Mehr News Agency, July 22, 2011.

Such statements are not rhetorical. When lawyers persist to defend the rights of their clients by publicizing due process violations in their cases, the Revolutionary Courts have no qualm in intimidating them, including with heavy prison sentences, loss of license, and sometimes forcing them into exile. Over the years, Iranian prisons have hosted scores of lawyers. Today, Abdolfattah Soltani is serving a thirteen-year sentence, while Mostafa Daneshjoo, Farshid Yadollahi Farsi, Amir Eslami, and Omid Behruzi are serving their seven and a half year sentence for “propaganda against the state and acting against national security.”

Nominating Sadeq Khalkhali as the Head of the Islamic Revolutionary Tribunal in February 1979 and mandating him to roam the country and summarily execute citizens was no accident. The goal of this pseudo-judicial institution was not justice then and it is not now. Successors to the first Shari’a Judge do not have to kill dissidents in great numbers today as Revolutionary Courts in the 1980s successfully eliminated all organized political dissent outside the Islamic Republic ruling factions. Regardless, the death toll is not negligible.

The Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation has collected reports and documented at least 13,690 executions (and extra-judicial killings) in the first decade of the Islamic Republic; more than 4,200 in the years 1990-2009, and 3,916 since 2010. The real numbers may be much higher, as many executions have never been reported. While reports of these executions do not always specify the sentencing courts, thousands of these executions are the outcome of Revolutionary Courts. Close to 80% of the executions in the past few years are drug-related cases, tried in Revolutionary Courts, in which defendants have no right to appeal.

The Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation has collected reports and documented at least 13,690 executions (and extra-judicial killings) in the first decade of the Islamic Republic; more than 4,200 in the years 1990-2009, and 3,916 since 2010. The real numbers may be much higher, as many executions have never been reported. While reports of these executions do not always specify the sentencing courts, thousands of these executions are the outcome of Revolutionary Courts. Close to 80% of the executions in the past few years are drug-related cases, tried in Revolutionary Courts, in which defendants have no right to appeal.

The functioning of Islamic Revolutionary Courts severely undermines judicial authority in Iran and violates a multitude of the country’s international obligations. It is time for the Islamic Republic’s leaders to address the legacy of destruction and hatred of these now permanent extraordinary courts and to close them down. The arguments justifying the need for a tribunal that fails to meet all standards of fairness was not convincing in 1979, and it is less so in a 36-year-old republic.

——————————————————————

[1]1. Crimes against national and international security,“moharebeh”(enmity with God) and “efsad e fel arz” (corruption on earth);

- defaming Ayatollah Khomeini and the Supreme Leader;

- plotting against the Islamic Republic of Iran, armed action, terrorism, and sabotage;

- espionage;

- smuggling and drug-related crimes;

- claims under Principle 49 (economic crimes) of the Constitution.

My Interrogator Said: You Are An Ass, And Asses Do Not Merit Human Rights

My Interrogator Said: You Are An Ass, And Asses Do Not Merit Human Rights