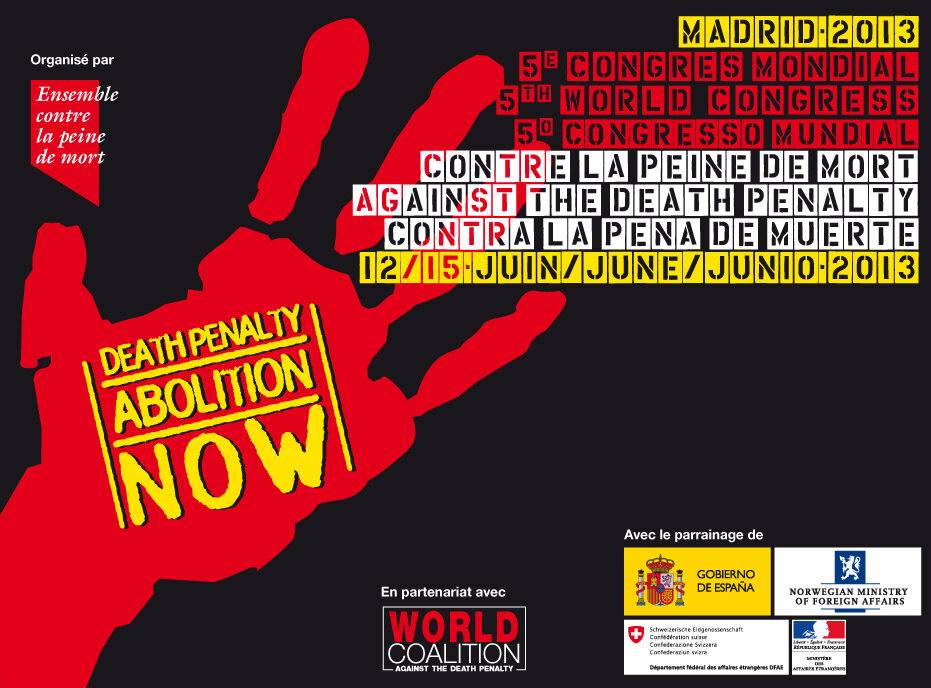

Expert Panel on Executions in Iran – 5th World Congress Against the Death Penalty in Madrid, June 13th, 2013

On June 13th the Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation (ABF), member of the World Coalition against the Death Penalty, joined allies in human rights from over 90 countries at the 5th World Congress against the Death Penalty in Madrid, Spain. The conference hosted a variety of experts and abolitionists against the death penalty worldwide. Topics included regional actors, executions of juveniles, the role of drug trafficking, and stories from victims’ families. There was also an abolitionist poster gallery and a final resolution to aid abolitionist groups in the fight against the death penalty. Many distinguished guests made appearances, including Iranian Nobel Peace Prize recipient, Shirin Ebadi.

ABF Executive Director, Roya Boroumand, was invited to speak on a panel about the death penalty in Iran. Other notable figures included the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on human rights in Iran, Ahmed Shaheed, Mahmood Amiri-Moghaddam of Iran Human Rights based in Norway, and Hossein Raesi, an Iranian attorney in Canada. During two hours of discussion, the group painted a grave picture of the current situation in Iran.

Mr. Shaheed gave a holistic review of Iran’s death penalty policies in contrast with universally recognized human rights norms. Many of Iran’s transgressions are in direct violation of treaties that Iran is a signatory to, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Article six of the ICCPR provides that every human being has the inherent right to life and shall not be arbitrarily deprived of that right. Mr. Shaheed stated that article six reminds signatories that “the death penalty may not be imposed if particular aspects of the covenant are violated” and that the Human Rights Committee has interpreted this article to include “the right to be promptly Iran systematically ignores international norms for due process by holding prisoners for years without charge, forcing confessions through the use of torture, withholding legal counsel, and assumin informed of one’s charges, the presumption of innocence, the right to legal counsel of one’s choosing, and a sufficient time to prepare one’s defense. It also includes the right to a hearing in the presence of an independent and impartial tribunal, the right to appeal, and clemency.” Later, Mr. Raesi discussed Iran’s lack of an adequate appeals process in drug trafficking cases. “Instead of an appeals process the verdict is sent to the Attorney General of Iran’s office for a quick review,” he said. “However, this is definitely not a suitable or sufficient replacement.”

Mr. Raesi’s time as an attorney in Iran gave him special insight into the inner workings of the regime’s practices. He confirmed that “the judiciary never officially announced some executions.” He also witnessed the aftermath of torture upon clients in custody, recalling, “The suspect’s teeth were broken by the police officer interrogating him.” Ms. Boroumand later added to this, telling the panel, “The manner in which [Iran’s criminal investigation office] conducts its business, including severe beatings, flogging, burning, and various other forms of torture has created a lethal interrogation environment.”g guilt in speedy trials with no appellate oversight. Mr. Shaheed collected more than 400 interviews over a six month period describing derogations from fair trial standards. “They often reported being held for periods ranging from a few weeks to years without charge and that they were subjected to frequent and severe psychological and physical torture for the purposes of extracting confessions,” he said. “Most individuals reported being denied access to a lawyer of their choosing, often described hasty trials, and their guilt appeared to be assumed by the tribunal.” In some cases, attorneys are even imprisoned. Ms. Boroumand illustrated this point by bringing up the Houtan Kian case. Houtan Kian is an Iranian attorney who has been imprisoned for two years after speaking out on behalf of his client who was sentenced to death by stoning. “The international community should not tolerate this,” she said.

Indeed, Iranian death penalty practices violate many international norms. Mr. Shaheed said that “over 80 percent of the capital crime sentences do not meet the most serious crime criterion under international law.” He stated that “the vast majority of these crimes are for alleged drug possession and trafficking,” but also include “adultery, blasphemy, alcohol consumption, and some economic crimes.” Ms. Boroumand pointed out that “the number of crimes punishable by death in Iran is astonishingly high: 87 compared to Pakistan’s 40.”

Iran also continues “execution methods that have been identified as unacceptable under international law,” Mr. Shaheed continued. The Human Rights Committee found that “the use of the gas chamber constitutes a cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment” and is “incompatible with human dignity.” Iran’s use of stoning is particularly cruel and inhuman in that “the size of stones is often limited to prolong human suffering and death.” The Iranian government’s response has been “deeply unsettling” by saying that stoning is not cruel or inhuman because it “allows for men who are buried up to their waist and women who are buried up to their chest a chance to dig themselves out and therefore escape from their punishment.”

The penal code in Iran allows executions for those who have “reach[ed] puberty,” which is defined as “nine years for girls and 15 for boys.” Mr. Raesi later added to this by discussing several cases in Iran. “I have here with me the verdicts of the criminal court and the Supreme Court of Iran regarding Fatemeh,” he said. “She allegedly murdered her husband at 17 while she was a high school student. I also have the verdicts for Abumoslem, 17-years-old; Ashkan, 15; Asadulla, 15, and; Amin, 17.”

Mr. Shaheed said the regime uses capital punishment as a “widespread tool for silencing dissent.” Notably, “the law now relies on what is called the knowledge of the judge as permissible means for defining crimes and punishment.” These provisions within the new penal code have expanded the scope of crimes such as “enmity against God” and “corruption on earth” to include remarkably vague charges such as “publishing lies” and “hurting the economy.” This discretion creates an environment where the regime may implore judges to rule for the death penalty in cases involving perceived political adversaries.

Drug charges result in more death sentences than any other crime in Iran. Mr. Amiri-Moghaddam presented charts showing that drug-related charges make up 73 percent of executions. Ms. Boroumand discussed situations in which individuals were executed for carrying as little as 18 grams of narcotics. Mr. Raesi emphasized the regime’s contradictions in punishment for drug charges by speaking of a client caught at the airport with seven kilograms of heroin but was never executed because exportation drugs is a lesser offense than typical possession. In fact, the conference held a separate panel on drug trafficking and the death penalty that centered mostly on Iran. The panel seemed particularly concerned that the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes (UNODC) provides funding to help Iran combat drug trafficking. Surprisingly, many of the donor countries are abolitionists.

“Members of Iran’s ethnic and religious minorities are particularly vulnerable,” Mr. Shaheed said. “Groups like the Kurds and Baluch, who reside in impoverished areas, are more likely to be attracted to drug trafficking and smuggling.” Mr. Shaheed noted that there are “allegations of indiscriminate killings and woundings of dozens of transporters that smuggle commodities such as tea, tobacco, and fuel across the border in order to make a living.” An overwhelming number of religious minorities are charged with national security crimes and although “they often shy away from politics, they are often seen by the government through the political and national security lens.”

While an attorney in Iran, Mr. Raesi witnessed arbitrary variation in sentencing for many non-serious crimes. He recalled a particular case in which a drug addicted client was publicly hanged with combatants of the state for the relatively minor offense of aiding an alleged criminal to escape. Mr. Raesi was sure that his client was unaware of his alleged co-conspirators’ plans, but it did not seem to matter to the judiciary who seemed more interested in deterrence. “Therefore, I believe that most of the executions that happen in Iran are inseparable from the major policies of the regime,” he said.

Ms. Boroumand gave the panel an overview of ABF’s database, “Omid” (“hope” in Farsi), which chronicles ongoing human rights abuses in Iran and is the most extensive human rights library in Farsi available. Ms. Boroumand told the panel that within Iran “no national mechanism is able to safely and systematically investigate executions and allegations of human rights violations, documentation, reporting and advocacy.” This makes third party information gathering of human rights abuses in Iran crucial. “Transition from the current authoritarian state in Iran will be a reality sooner or later,” she said. “Both the Memorial and the human rights library, which contains multiple translated texts regarding the capital punishment, can bring to light the arbitrary and ineffective nature of the death penalty and engage the public.”

Nevertheless, there was considerable hope for the future. All of the panel experts agreed that unlike many other rogue states, the Iranian government is susceptible to international critique. In some cases, outcry from the international community has saved several individuals from execution, particularly children. Mr. Amiri-Moghaddam has data indicating that public executions decrease during times of international media attention, but spike again shortly after to reassert government control. For example, “After the contested presidential election of 2009, we witnessed a surge in the practice of public executions.” He believes international attention could curb this pattern by “increasing the cost of these executions by international attention” and that “when the world is watching Iran, you don’t see…executions…but before and after you [see many executions].”

There was wide consensus on the panel that the international community should ignore the regime’s criticism that universal human rights are insensitive to Iran’s cultural, religious, and historical contexts. Political figures are often elected under promises of increased personal freedoms, demonstrating that universal human rights exist within the Iranian zeitgeist. Ms. Boroumand believes that other human rights organizations should continue documenting the regime’s abuses, saying, “Highlighting the flaws of the judicial process in hundreds or thousands of cases strengthens the argument about the right to fair and impartial justice and leads ultimately to a crucial debate on capital punishment.”

There was wide consensus on the panel that the international community should ignore the regime’s criticism that universal human rights are insensitive to Iran’s cultural, religious, and historical contexts. Political figures are often elected under promises of increased personal freedoms, demonstrating that universal human rights exist within the Iranian zeitgeist. Ms. Boroumand believes that other human rights organizations should continue documenting the regime’s abuses, saying, “Highlighting the flaws of the judicial process in hundreds or thousands of cases strengthens the argument about the right to fair and impartial justice and leads ultimately to a crucial debate on capital punishment.”

The panel agreed that the international community should take action by closely monitoring funding to Iran through the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime drug trafficking program. Mr. Shaheed stated that “all organizations and states that oppose Iran’s use of the death penalty should ensure that no funds intended for prevention are used for arrests as they may ultimately lead to executions.” Further, “the correct cause of action might be to limit support altogether until such time that all relative certainty can be established that funding will not be used contrary to UN and international rights norms.” Mr. Amiri-Moghaddam agreed, “The donor countries should say that as long as there is capital punishment for drug related charges that we will not cooperate with you.”

My Interrogator Said: You Are An Ass, And Asses Do Not Merit Human Rights

My Interrogator Said: You Are An Ass, And Asses Do Not Merit Human Rights